| |

Leading the industry to the Crash of 2012 |

|

| x |

In the eyes of the industry’s

largest grading laboratories, it was

only a matter of time before this

day would come. Synthetic, or labgrown,

colourless diamonds

created using the chemical vapour

deposition (CVD) process are

becoming more common in the

market. And not everybody’s being

honest about what they are selling.

This spring, a parcel of

hundreds of CVD synthetics was

submitted to the International

Gemological Institute in Antwerp,

while another, albeit much smaller,

group of CVD synthetics surfaced

at the Gemological Institute of

America’s Hong Kong lab in June.

Diamonds in both parcels were, for

the most part, of high colour and clarity and ranged in size from 0.30

carats up to 0.70 carats.

This pair of parcels shared at

least one other common trait:

neither was submitted with proper

disclosure. In the case of the

diamonds in Antwerp, the dealer

who submitted the lab-grown

diamonds paid natural prices for

them and, according to those

involved with the situation, was

unaware he had purchased labgrown

stones.

News of what had happened

in Antwerp sent ripples through the

industry worldwide and in Belgium,

ground-zero for submission of the

larger parcel of undisclosed

synthetics, the country’s federal

police have opened an

investigation. |

x |

| |

|

|

| |

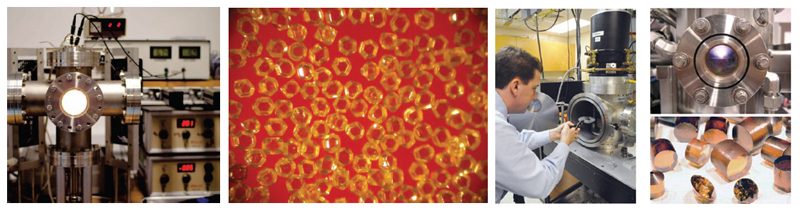

1) The undisclosed lab-made diamonds

detected by IGI 2) Mr Tom Moses 3) Mr Peter Yantzer |

|

| |

For the industry’s grading

labs, however, the identification of

synthetic diamonds is not breaking

news but a reality that they have

spent a decade preparing to deal

with, and one that leaders say they

are equipped to handle. Tom

Moses, senior vice president of the

GIA lab, likens the situation to that

of a student who’s been dutiful

about doing his homework and is

well prepared for an upcoming

exam. “It makes this issue less

daunting,” he says. “We have a lot

of respect for it. We have invested

a lot in it. But I must say we have a kind of quiet confidence that we

really feel that we can deal with

this situation.”

The science behind synthetics

While the heads of the world’s

largest grading labs can’t give an

exact year, they all date the

practice of screening for synthetics

back to the late 1990s. Peter Yantzer,

executive director of American

Gem Society Laboratories (AGS

Lab), specifically recalls making a

trip to London around that time

with AGS CEO Ruth Batson. The

purpose of the trip: to learn about

two new machines being rolled

out by diamond giant De Beers,

the DiamondSure and the

DiamondView.

Shortly after this trip across

the Atlantic, first-generation

DiamondSure and DiamondView

machines arrived in the United

States. Today, they are key

components of the behind-thescenes

work that allows

gemmologists to sort the natural

from the man-made. “De Beers,

they saw what was going on,”

Yantzer says. “Kudos to them.” |

|

| |

|

|

| |

As the GIA noted in an article

in its summer 2009 edition of Gems

& Gemology, knowledge of

diamond type is what helps labs

better determine if a diamond is

natural, treated or synthetic.

According to the article, which

cites decades of research,

diamonds can be sorted into one

of two broad Type categories. Type

I diamonds, which contain nitrogen

impurities, and Type II diamonds,

which lack the former. The Types

are further broken down in Type Ia

(aggregated nitrogen impurities),

Type Ib (isolated single nitrogen

impurities), Type IIa (no nitrogen or

boron impurities) and Type IIb

(boron impurities). (Type I

diamonds are broken down further

into Types 1aA and 1aB.). Moses

says that more than 95 percent of

natural diamonds turn out to be

Type Ia but that it is “difficult” to

grow Type Ia diamonds in a lab.

CVD synthetics of any colour are

Type IIa or IIb.

When gemmologists place a

diamond in the DiamondSure, they

are checking for a spectroscopic

characteristic of a Type Ia

diamond; basically to see if the

diamond is instantly recognizable

as natural or if it needs to go on for

further testing. Those diamonds

flagged by the DiamondSure go

on for further analysis and expert

interpretation, which can include

De Beers’ other machine, the

DiamondView. The DiamondView

blasts stones with high-energy UV

radiation to allow for real-time

imaging of fluorescence features

in diamonds, exposing their growth

structure.

Moses says that diamonds

grown in a lab using the CVD or

HPHT process exhibit a telltale

growth pattern that consistently gives them away as being

manmade. For example, the crop

of 10 synthetics recently submitted

to GIA Hong Kong exhibited

“typical CVD growth striations”

when placed in the DiamondView,

the GIA said. “No matter what you

do to treat or disguise synthetics,

those two growth features, in HPHT

and CVD, cannot be removed. It

can’t be changed,” he says. This

DiamondView fluorescence image

of a diamond grown using the

high-pressure, high-temperature

process (HPHT) shows the four-fold

growth sectors typical of HPHT

synthetics. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

4) Mr Roland Lorie |

|

| |

Another aspect of the

synthetic market that Moses doesn’t

see changing is the ability to

determine if a stone is natural or

synthetic with a single tool. During

a presentation to the Diamond

Manufacturers and Importers

Association of America in New York

last month, Moses shot down the

idea of the development of a

“black box,” one instrument that

can wholly determine if a diamond

is synthetic or natural. Moses also

has expressed skepticism about the

DiamaPen, the $199 pen-shaped

device said to be able to instantly

discern lab-grown yellow

diamonds from their natural

counterparts. The DiamaPen’s

capabilities currently are being

tested by both GIA and IGI.

Mitch Jakubovic, director at

EGL USA, concurs that development

of a so-called black box seems

unlikely. “Although we have not

tested this new device (the

DiamaPen), the development of a

single inexpensive unit that can

instantly identify mined diamonds

from synthetics seems very unlikely,”

he says. “In some instances, multiple

tests may be needed to determine

if a diamond is a natural or lab

grown and it would be very difficult

to imagine a machine that can

implement all those pieces.” He

adds that some of the advanced

pieces of equipment used in the

process generate graphs that are,

in turn, read and interpreted by

senior researchers, all of which

create a story about each

individual stone.

The labs’ role

The latest crop of undisclosed

synthetic diamonds to appear on

the market — the 10 diamonds

submitted to GIA Hong Kong —

were the first such submission from

this particular client, Moses says.

While GIA does not disclose

client names, the July Gems &

Gemology eBrief announcing the

submission mentioned one very

familiar name: Gemesis. The labgrown

diamond company is also

the one linked to the large parcel of synthetics submitted to IGI in

Antwerp, though the company has

issued public denials of its

involvement. The eBrief stated that

the diamonds had gemmological

and spectroscopic features “similar

to those observed in Gemesis CVD

synthetic diamonds, suggesting

that post-growth annealing at high

temperature was used on the

diamonds to improve their colour

and possibly their transparency.” |

|

| |

|

|

| |

None of the heads of the

industry’s largest grading labs

expressed surprise that synthetic

diamonds are hitting the market in

larger quantities, or that they are

not always being represented

properly. The technology for

growing colourless diamonds using

the CVD process has improved. In

turn, the stones themselves are

larger and of higher quality and

are showing up more frequently in

grading labs around the world.

It was little more than two

years ago, May 2010, when the

GIA identified its first near-colourless,

CVD-grown diamond that

weighed more than a carat.

“Clearly, CVD synthetic diamonds

of better quality and size are being

produced as the growth techniques

continue to improve,” the GIA

stated at the time.

It’s not unnatural that industry

players looking to turn a profit

would resort to selling synthetic

stones as natural. As Jerry

Ehrenwald, president and CEO of

IGI North and South America, put

it, “Since the moment synthetic

diamonds were commercially

available the ability to either

consciously or not consciously

defraud someone was able to

happen. It was just a matter of

time.” The introduction of the

seemingly inevitable criminal

element, however, raises questions

about the labs’ role in bringing

those that attempt to defraud to

justice.

At GIA, Moses says that the

first time a client submits synthetic

diamonds without proper

disclosure, such as just happened

in Hong Kong, the lab informs them

that the stones submitted were lab

grown and issues a synthetic

diamond report. “If that happens

one time, it’s not really appropriate

for GIA to take action at that point,”

he says. If it keeps happening,

though, he says the GIA has the

right to stop doing business with

the client and, if circumstances

warrant, to notify appropriate trade organizations, trading bourses and

even law enforcement. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Other labs agree on making

the industry aware but stop short of

wanting to be the ones to bring in

the law. IGI Worldwide co-CEO

Roland Lorie says that when the

parcel of hundreds of undisclosed

synthetic stones came into their

lab, it contacted the Belgian

Federation of Diamond Bourses.

“People come to us because we

are the experts. We are not the

ones to decide who is dealing

honestly or not,” he says, when

asked why the lab did not reach

out to law enforcement authorities.

“People come to us just to know

what they have in their hands,

because a lot of times they don’t

know.

“We are not there to take up

the role of any of the industry’s

authoritative and regulatory

associations,” he says. “Otherwise,

there’d be no reason for those

associations to exist.” If IGI

Worldwide perceives that there is a

potential problem with a client,

Lorie says, then it contacts the

diamond bourses, which are

Mr Roland Lorie

responsible for the integrity of their

members. He says IGI is still doing

business with the unnamed client

that submitted the parcel of

hundreds of undisclosed synthetics.

“He didn’t know, and the bourses

agreed that he didn’t know,” he

says. “The person who sold it to him

probably knew.”

As to whether or not members

of the industry are being aggressive

enough in the case, Lorie’s answer

is, simply, that the industry should

be aggressive. “For the moment, I

haven’t heard anything. I didn’t

hear about anyone that was

punished or expelled or suspended

from the bourse,” he says.

Jakubovic says EGL also

would notify industry organizations

if confronted with a situation

involving hundreds of synthetics,

such as IGI was, though he is quick

to point out that EGL USA hasn’t

had that happen. The lab has had

many synthetic diamonds

submitted without disclosure over

the years but only in smaller

amounts-a few stones here and

there from varying sources — and

the lab doesn’t believe there was

intent to defraud in the vast majority

of those cases. “There are definitely

people in this industry who are

inappropriate, without a doubt,”

he says. “But is it our place to get

law enforcement involved? I don’t

think so.”

However, Jakubovic says, if

faced with an “extreme

circumstance” the lab would

consult with its legal advisors. “This

has to be contained. The end

consumer has to be protected,” he

says. “Our responsibility as a major

laboratory has grown and will

continue to grow as these are in

the marketplace.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Undisclosed Synthetics pose a Dilemma By: Chaim Even-Zohar and Pranay Narvekar |

|

| |

“The crash of 2008 was far more benevolent

than the coming diamond crash of 2012,” remarked a

large DTC sightholder, explaining the difference as

follows: “In late 2008 and early 2009, the business

came to a virtual standstill. We didn’t buy, nor did we

sell. Accounts receivables came in. Our banking debt

went down. In early 2009, when the business gradually

normalized, our activity resumed, prices stabilized –

and we emerged from the crisis without major damage.

There were hardly any bankruptcies.”

Continues the sightholder: “Today, it is different.

There is activity, we buy DTC sightboxes and, month

after month, we lose between 10%-20% on the polished

we sell. We are destroying value; we are creating a

‘hole’ that is growing month after month. The ‘smart’

DTC sightholders last week deferred their purchases –

which is a code name for ‘leaving goods on the

table’.” De Beers’ management reportedly takes

mistaken pride in

“defending its prices.”

However defending

unsustainable prices

that cause lasting

damage to clients, the

market and to De Beers

itself is a fallacy, a

delusion, that will

backfire.

By our estimates,

some 20-25 percent of

the last sight was not

taken. De Beers sold

$100 -$125 million less

than it had budgeted.

And those sightholders who didn’t take their full

allocations are the smart ones. As one DTC broker

intimated: “DTC prices are still some 7%-10% too high

and they must come down. So those who didn’t take

the goods now will pay less for them at the following

sights.”

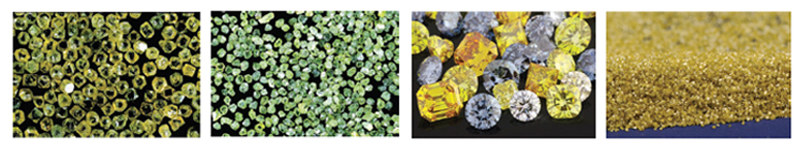

Failure of Price Management

One must differentiate between two separate

issues: the extreme price volatility of rough, and the widening gap between the rough prices and those of

the resultant polished. If one takes the end of 2007 as

an arbitrary point of basic price equilibrium, which

was before the world’s financial markets imploded,

we see that the industry came through the crisis well

intact, and by the third quarter of 2009, the rough and

polished price movements again were in equilibrium –

albeit both at a lower price level. Whoever bought

rough at that time would be able to sell the resultant

polished at break-even or profitable prices. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

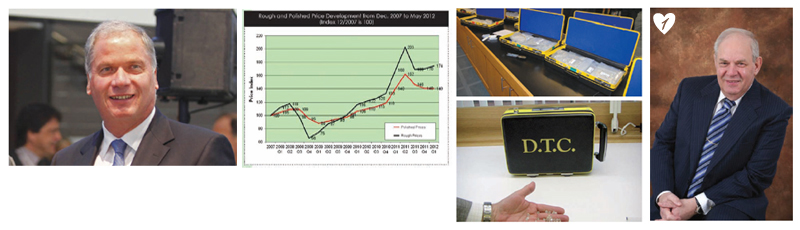

Mr Chaim Even Zohar |

|

| |

Throughout 2010, admittedly a profitable year

for the diamond industry, both rough and polished

prices rose more or less in tandem; there was a

manageable gap in the pace of growth between

rough and polished. Keeping rough somewhat“expensive” is ultimately a time-proven way to push

polished upwards. There is also a natural time gap,

where price increases work their way through the

pipeline, and, throughout 2010 and 2011, many traders

were willing to speculate and buy rough at (too) high

prices, “assuming” that polished would have increased

by the time their resultant output reached the markets. They miscalculated in a big way.

Thus in 2011, the market went into a steep upward

spiral price-wise: by the third quarter of 2011, rough

prices had doubled since the third quarter of 2009,

when rough and polished prices had been in

equilibrium. Polished price growth, however, then

lagged some 25 percent behind the corresponding

rough. That is unsustainable. Then came the third

quarter 2011 crash, and most diamond companies

literally saw the profits made earlier wiped out. Though

producers still made record profits, many of their

clients lost money and were left with stocks that had

lost, and still were losing, enormous value.

Looking at the demand and supply

fundamentals, it became clear that rough prices

needed a downward correction to close the gap with

the polished prices. At the end of 2011, Mumbai/

Dubai’s Pharos Beam Consulting and Tacy Ltd.

predicted that rough prices needed to fall – and they

did. [This was also stated by us at the PDAC in Toronto

in early March 2012 as widely reported by Reuters,

Forbes and elsewhere.] It was clear that De Beers had

dropped its time-honoured policy of “maintaining

sustainable prices,” and it was now using – or abusing

– its market power as the largest and dominant

producer to “overshoot” price-wise. That’s where we

still are today.

The new De Beers management, after Philippe

Mellier assumed the helm in mid-2011, seems to pursue

a short-sighted policy of driving up rough prices while

totally disregarding the polished markets. It also seems

to have little consideration for the company’s

customers who distribute or manufacture De Beers’

output, and who should have an inherent right not to

lose money. De Beers doesn’t have ill intentions; the

miner simply lacks good market feedback. Mellier

may not have realized that clients fear telling him

straightforward “how bad things are” – especially in a

period preceding client selection. De Beers

overestimated the demand side; it assumed supply

shortages that were more imaginary than real. That is

still the case today.

If rough and polished prices had been in

equilibrium by the third quarter of 2009, two years later,

that gap had widened by more than 25 percent. DTC

sightholders don’t need sophisticated economic

models to know what went wrong – they see that they

are losing vast amounts when manufacturing their

DTC sight boxes. At the June 2012 sight, the sightholders

rebelled. We are not sure whether this is recognized as

such in London – at both De Beers and at Anglo

American. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Sightholder Rebellion

At the end of the most recent sight, DTC brokers

and representatives, realizing how many goods were

“left on the table,” were quick to remind clients that

under the terms of the present DTC sightholder contract,

not taking one’s ITO (Intention to Offer – the pro-forma

supply commitment by the DTC) will “potentially lead

to the reduction in the starting point of future ITO’s

when contractual allocations are not fully taken up

during this ITO period.” [Quote from a broker’s June

internet sight newsletter.]

Indeed, many DTC clients face a dilemma: Will

I do what is good for my business and refuse to buy

rough that guarantees financial losses on the sale of

the resultant polished, or do I honour my commitment

to the DTC to purchase whatever is offered to me at

whatever price it is offered? There is no unequivocal

answer, though I told one friend facing this dilemma

that he should stop being a sucker and ensure the

financial solvency of his business; by simply transferring

money to the DTC month after month at losing prices,

he will not be around anyway when the next ITO is

formulated. So why worry about the level?

On a different level, it seems to reason that De

Beers is bluffing. It cannot afford to reduce ITOs next

time around. It cannot be sure that others will indeed

be willing to take these goods. Nor can it sustain the

current absurdity where DTC sight boxes are auctioned

by Diamdel at 7-10 percent BELOW the DTC sight selling

prices. Some small lots have gone at even far greater

discounts to DTC box prices. This is as absurd as it is

ethically and morally questionable. Sightholders who

have made a long-term purchase commitment to the

DTC end up paying substantially more for DTC goods

than those occasional and non-committed buyers

participating in Diamdel auctions.

Destroying Brand Value

For Diamdel to destroy financial and DTC brandequity

value by even considering undercutting DTC

sightholders is more a manifestation of De Beers’

management’s despair to sell goods than anything

else. If, hypothetically, De Beers is budgeted to sell,

let’s say, US$7 billion worth of rough in 2012, of which

US$5 billion would go through the ITO system, and if,

theoretically, clients leave US$1 billion of ITO goods on the table, the ITO format would say “new ITO’s will be

at a level of US$4 billion, rather than US$5 billion.”

Irrespective of the way the ITO system works, in

the present so-called new “dynamic pricing” system,

most sightholders will not be willing to get “rewarded”

with higher ITO’s. I also don’t think that Diamdel clients

would want to become sightholders, as at auctions

they pick up boxes at BELOW the cost price of the

boxes and they are spared the prospects of having to

sell DTC sight allocations at discounts. By lowering the

ITO’s the next time around, De Beers will be creating

another obstacle for itself on how to move the goods

onto the market. Actually, ITOs have become MORE

important to De Beers than to clients.

Message Manipulations

De Beers is managing the market (or, we should

say, its own market) through certain manipulations

including controlling its “messages” (such as saying it

is “leaving goods in the ground”). Indeed, the internet

sightletter remarks that “for the second consecutive

Sight in the new contract period, the DTC was unable

to meet its full ITO commitments to many clients across

a range of boxes due to shortfalls in forecast

availabilities.”

We find that hard to believe. De Beers has made

a commitment to the Botswana government to sell to

it some 10-15 percent of its output for domestic window

sales. The Botswana government has created a

marketing company, Okavango Diamonds, which, at

any time, is allowed to purchase this entitlement. So

far, it hasn’t done so. The arrangement doesn’t work

retroactively – in other words, goods which Okavango

has not purchased so far can be freely sold by the

DTC. For this, and other reasons, I don’t “buy” the

shortfall argument. It should have a few hundred

millions in stock that had been earmarked for

Okavango.

Let’s not overlook that Mellier’s policy, expressed

in the company’s 2011 financial review, is that “De

Beers produces in line with demand from our

Sightholders. … In the second half of the year [2011], as

it became clear that the market was beginning to

cool, we made the conscious decision to focus our

resources on maintenance and waste-stripping

backlogs. By addressing these issues when we did, we

have put our mines in a strong position to ramp up

production, as Sightholder demand dictates, in 2012.”

Saying “we don’t have the goods” sounds better

than admitting that its clients will not take the goods at

current prices; it will also enhance the atmosphere of

rough shortages. The DTC, at the June 2012 sight,

reportedly also declined to sell some additional goods

requested by some clients, which will further enhance

the “shortages argument.” (I find this a rather strange

decision since, when the DTC ultimately will sell these goods, it will be at lower prices.) |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Sense of Confusion

Watching De Beers and listening to DTC

sightholders and other stakeholders, one gets the

sense that De Beers portrays a lack of direction, a lack

of confidence and conviction among management

and down to the sales team. Those attending one of

the client and management functions at the last sight

underpin the notion that all is not well among DTC

decision makers. Some of this is understandable: the

transition to Anglo American management and the

move to Botswana create considerable anxieties

among many employees. They are all waiting for

Anglo.

We have written before that the company’s

management has become much more of a spreadsheet

exercise. Clients aren’t that important – and they

are replaceable. What seems clear is that the “good

old days,” when sightholders were enjoying doubledigit

premiums on the sight boxes, are something of

the past. These days will not come back. That changes

something in the relationship equation. One might say

that, in the past, De Beers “bought” client loyalty as it

was really worth it to be a sightholder. Now, De Beers

needs to “earn” client loyalty – and they don’t seem to

be making a great effort anymore.

Even though Mellier stresses in recent interviews

that it is recognized that diamonds are “a different

kind of commodity,” I am not sure that Mellier knows

what that means or that I understand what he meant.

Maybe it is our problem.

While Anglo American decided to buy out the

Oppenheimer family’s stake in De Beers, Rio Tinto, BHP

Billiton and, most recently, Alrosa’s 51 percent

shareholder, the Russian federal government, have all

put up sale signs on their respective diamond

businesses. These changes affect nearly 70-75 percent

of the entire rough diamond supplies. It was a surprise

to many that the Oppenheimer family decided to

move out of the business altogether. (If his family,

especially his sister Mary Slack and her four daughters,

needed money – he still could have kept a sizeable

share in the business for himself and son Jonathan.)

These actions raise the basic questions of what

the future holds for the diamond mining industry and

what it will mean for companies in the downstream

diamond businesses. Are these companies really selling

the golden goose, or is it simply that the goose no

longer lays golden eggs? |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Managed by Employees

One must look beyond De Beers – and many of

the industry changes we are witnessing are not of DeBeers’ making. On rough pricing, the industry has

already seen a pivotal shift in how rough is priced and sold. That is the industry legacy of the crisis. Diamond

producers have come to believe that the best way to

manage a slowdown is to keep the goods in the

ground, something which other industries have also

followed. There, the diamonds are safe, can be

extracted when required, and don’t even run afoul

with anti-trust regulators.

What has undoubtedly changed for the worse is

the perspective of the producers themselves. These

businesses are no longer run by people who own

them. Instead, the businesses are managed by

professional managers appointed by the boards.

That’s the main change we see now at De Beers,

where, by tradition and by management contract, the

Oppenheimer family ultimately made the final

decisions.

These professional managers may or may not

have diamond business experience. Their sole focus is

the profitability of the company over the duration of

their tenure, which might be between three to five

years. For some of these managers, reducing rough

production seemed like the golden wand that could

help them push up volumes.

The “benevolent” producer does not exist

anymore, with all the large producers purely focused

on maximizing their prices, rather than ensuring the

basic health of the pipeline. A professional manager

has to justify to his board that he is securing the best

possible prices during the course of his tenure. He is not

really concerned about whether his customers are

really profitable or whether the producer is really the

supplier of choice. That would be the problem of the

next manager.

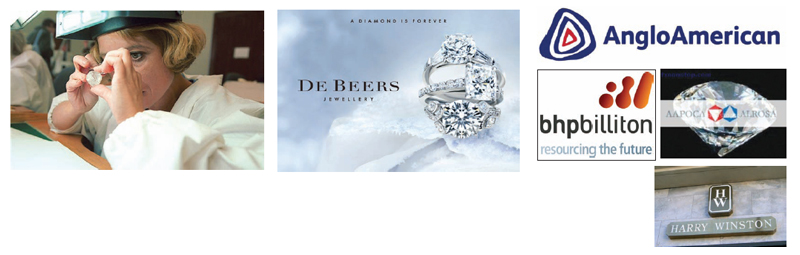

Prices over Sustainable Levels

Looking just at the last 12 DTC sights or so, one

can distinguish price movements in both directions

ranging from 25 percent upwards to 25 percent or

more downwards, depending on the boxes. DTC sight

box comparisons are complex, as in many instances

the composition of boxes have also seen changes –

and if a box containing from four to eight grainers

changes the ratio of sizes, this impairs the validity of

comparisons. Nevertheless, we believe that our charts

are broadly representative.

The chart shows the five categories of boxes

where DTC average prices were the lowest, when

compared to the prices in April 2011.

The chart shows the five boxes where DTC average

prices moved the highest, when compared to the DTC

box prices from April 2011 to today.

In most of these boxes, it’s interesting to see that

the average price seems to have actually increased

by up to 29 percent between the first and the fifth sight

of 2012.

|

|

| |

We do express some caution. These prices are

based on a simple average of individual boxes

constituting each category. They do not account for

the actual carats sold and, hence, may not necessarily reflect the actual mix provided within the boxes and

across boxes. Hence, these might not necessarily reflect

the average price achieved by DTC.

Russians followed DTC pricing policy. Their goods

are also priced much above market – in same if not

higher ranges than DTC. Alrosa’s product mix is different,

more smaller and better quality diamonds, where

prices moved up much more DTC Prices peaked in

July/August of 2011. At that point of time, most industry

players considered DTC rough prices about 10 percent

higher than what was sustainable. Over the course of

nearly one year, polished prices have dropped about

15 percent, while DTC prices also seem to have dropped

about 13 percent, which would mean that the current

prices would also be about 10-15 percent above

sustainable levels. |

|

|

|

|

| |

The Prospects of De Beers

Looking at a crystal ball, what is the likely

outcome for De Beers for its current supply and pricing

policies? We believe that it is more than likely that:

De Beers will lose market share to other producers.

Management may not meet its profit targets –

and staff may miss out

on bonuses.

De Beers may run

into more cash-flow

challenges (if there are

more sights where

US$100-US$150 million is left on the table.) This requires

reliance on Anglo American’s deep pockets. the

rudest awakening will come when De Beers’

management will wake up one morning to see that

the goods left in the ground today cannot be sold at

a higher price tomorrow.

Reducing rough supplies when you are not a

near-monopoly is

essentially a

suicidal move, with

other producers

(read Alrosa, BHP

Billiton, Rio Tinto,

Harry Winston

Diamond Corp.,

Gem Diamonds,

Petra, etc.) laughing their way to the bank. De Beers

inevitably will change its course, as survival is a stronger

instinct than ego, but the damage might be irreparable

if the changes aren’t done sooner rather than later.

The market is heading for three difficult years –

but De Beers will underperform other producers in

terms of profits and will lose market share. In the

diamond business, we are not still getting out of the

last crisis, we are heading into a new one at full speed.

True, that may not be up to De Beers. But De Beers is

making sure that it is positioned in a worse place than

other producers. This is in nobody’s best interest –

nobody! |

|

| |

|

|

|